The Economics and Statistics Division maintains archives of previous publications for accountability purposes, but makes no updates to keep these documents current with the latest data revisions from Statistics Canada. As a result, information in older documents may not be accurate. Please exercise caution when referring to older documents. For the latest information and historical data, please contact the individual listed to the right.

<--- Return to Archive

For additional information relating to this article, please contact:

December 16, 2019STUDY: MEASURING THE GIG ECONOMY Statistics Canada released a study today regarding the measurement of the gig economy using administrative data. Highlights of their findings are reported below.

The gig economy is a much-discussed global phenomenon. This term is broadly referring to less structured and non-traditional work arrangements. Gig workers are defined as unincorporated self-employed workers who enter into various contracts with firms or individuals to complete a specific task or to work for a specific period of time. This includes unincorporated self-employed freelancers and on-demand workers hired for jobs mediated through online platforms such as Uber, TaskRabbit, Upwork, Fiverr and Freelancer.

This study introduces a clear methodological framework to identify gig workers. It uses administrative data from various Canadian administrative data sources. This study used the Canadian Employer-Employee Dynamics Database (CEEDD). The CEEDD T1 files covers all Canadian taxfilers. Statistics Canada constructed Financial Declaration (FD) files are better suited for analytical purposes. On an annual basis it includes all unincorporated self-employed workers in Canada. The data is currently available from 2005 to 2016. The important element for this study is that it combines the tax data with 2016 census microdata and Labour Force Survey (LFS) to fill in the information gaps.

Abraham et al. (2018) introduced a methodological framework for identifying gig workers based on the characteristics of their work arrangements and how theses are reported in tax data. This study’s methodology to measure the share of gig workers in the Canadian labour force is consistent with Abraham et al. (2018). The methodology makes a distinction between gig workers and traditional employees with wages and sole proprietors who own established business.

The study computed self-employment rates and examined basic differences in self-employment rates in survey and administrative data. The comparison across the three data sources shows substantial differences in the estimated shares of self-employed workers in 2016. The share of incorporated self-employed workers in the census data (4.4%) is less than half of the corresponding share in CEEDD data (9.5%). The estimated share from the LFS fell between the estimated shares from census and administrative data (7.1%).

Gig workers were 8.2 per cent of the total number of workers in 2016. The study computed the net total annual gig income for each gig worker in 2016, the median income from gig work was $4,303. Among gig workers, 48.6% had no wage-earning job and reported no employment income, while 36.3% had one wage job and about 15.1% had multiple wage jobs.

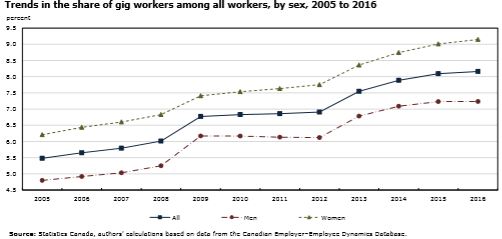

The estimated overall proportion of gig workers has been rising over the past decade. The share of gig workers among all workers in Canada rose from 5.5 per cent in 2005 to about 8.2 per cent in 2016.

The gig worker trend shows two sharp increases between 2005 and 2016. The first increase corresponds with the 2008/2009 recession, with a larger increase for men than for women. The timing of the increase suggests that the growth in the share of gig workers during those years can be largely attributed to push factors such as declining employment prospects. While the share of female gig workers continued to increase immediately after the recession (from 2009 to 2012), the share of male gig workers slightly declined during this period. The second sharp increase was observed around 2012/2013. After 2012, growth in the share of gig workers was higher for women than for men. In all years the share of gig workers was substantially higher among women than men and this gap widened over time.

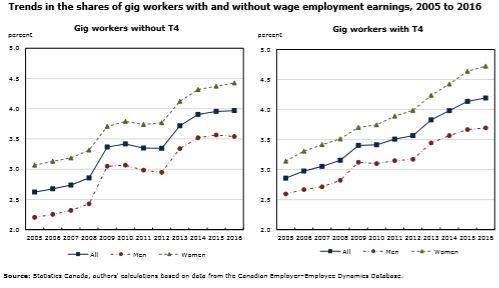

The trends in the shares of gig workers are shown separately for gig workers with and without wages or salaries. Gig workers with no wage earnings responded more strongly to both push factors (i.e recession, inability to find traditional employment) and pull factors (i.e. platform proliferation, work flexibility).

T4 earnings dropped significantly in the year an individual entered in gig work (year 0), suggesting that entry into gig work is generally preceded by a decline in non-gig income. This decline was larger for men than for women in the study.

The study considers the characteristics of gig workers that are available in tax data, such age marital status, area of residence and industry of gig work. The results suggest that no age group dominated the age distribution of gig workers were spread more or less evenly across the entire age spectrum. However, the prevalence of gig workers was especially high in the category for those aged 65 and older as fewer individuals work in general. About62.4% of all gig workers in 2016 were married or cohabited, while about 28.9% of male gig workers and 24.5% of female gig workers were single (never married). However, men (8.6%) and women (10.7%) who were divorced, widowed or separated were more likely to be gig workers than either married or single men and women.

The shares of gig workers among all workers was higher where opportunities for gig work were greater, specifically in the three regions that have major urban centres—Quebec (Montréal), Ontario (Toronto) and British Columbia (Vancouver).

The study shows that 49.8% of male gig workers and 45.2% of female gig workers belonged to the lowest two quintiles of the total income distribution.

The study shows male gig workers worked in professional, scientific and technical services (19.0%); construction (12.4%); and administrative and support, waste management and remediation services (10.6%). Female gig workers were concentrated in health care and social assistance (20.2%) and professional, scientific and technical services (17.4%).

The industry with the highest share of male gig workers was arts, entertainment and recreation (15.6%), which is the industry that originated the term “gig work.” A high prevalence of gig workers was also observed in health care and social assistance (13.3%), educational services (11.3%) and real estate and rental and leasing (10.8%). Among women, the industry with the highest share of gig workers was other services (except public administration) (20.1%), a broad category that includes personal care providers, cooks, maids, caretakers and nannies.

Statistics Canada: Measuring the gig economy in Canada using administrative data

<--- Return to Archive