Species at risk in Nova Scotia listed by status category.

American Marten endangered

Cape Breton Population - Martes americana - 2001 / Mainland Population - Martes americana - listing pending

The Cape Breton population of Marten is likely less than 50 animals. At present there is no evidence of breeding and there has been extensive loss and degradation of suitable habitat. Marten were trapped extensively throughout Nova Scotia since the 1700's until the season was closed in the early 1900's due to low numbers. The species was thought to have been extirpated from the mainland and several re-introductions have been attempted. There have been some very recent records of Marten in southwest Nova Scotia. However, the status of the Marten on the mainland is considered "data deficient." More research is required.

The Cape Breton population of Marten is likely less than 50 animals. At present there is no evidence of breeding and there has been extensive loss and degradation of suitable habitat. Marten were trapped extensively throughout Nova Scotia since the 1700's until the season was closed in the early 1900's due to low numbers. The species was thought to have been extirpated from the mainland and several re-introductions have been attempted. There have been some very recent records of Marten in southwest Nova Scotia. However, the status of the Marten on the mainland is considered "data deficient." More research is required.

American Marten recovery plan 2007 (Cape Breton) (PDF 213 kB)

American Marten status report (PDF 696 kB)

American Marten recovery plan (mainland population) (PDF 1 MB)

Atlantic Whitefish endangered

Coregonus huntsmani - 2002

The Atlantic whitefish is a species endemic to Nova Scotia, meaning that it breeds nowhere else in the world. In Nova Scotia it is found only in the Tusket and Petite Riviere watersheds and may have been extirpated from the Tusket River system. Little is known about this species and no population estimate for the species exists. Past and present threats to the species include: hydro-electric development, predation by non-native fish species (e.g. chain pickerel, smallmouth bass), acidification and fishing.

The Atlantic whitefish is a species endemic to Nova Scotia, meaning that it breeds nowhere else in the world. In Nova Scotia it is found only in the Tusket and Petite Riviere watersheds and may have been extirpated from the Tusket River system. Little is known about this species and no population estimate for the species exists. Past and present threats to the species include: hydro-electric development, predation by non-native fish species (e.g. chain pickerel, smallmouth bass), acidification and fishing.

Atlantic Whitefish recovery plan (PDF 4 MB)

Bank Swallow endangered

Riparia riparia - 2017

The Bank swallow is a small brown bird that feeds almost exclusively on flying insects. This swallow breeds in colonies and excavates nesting burrows in the eroding banks of coastal cliffs and other steep vertical soft soil faces, such as gravel pits. Their numbers have declined by about 30% over the past 10 years across Canada, and considerably more in Nova Scotia. A combination of factors, including loss of nesting habitat, reduced availability of insects, and threats encountered along the winter migration route and at overwintering areas in South America, have reduced the abundance of Bank swallows.

The Bank swallow is a small brown bird that feeds almost exclusively on flying insects. This swallow breeds in colonies and excavates nesting burrows in the eroding banks of coastal cliffs and other steep vertical soft soil faces, such as gravel pits. Their numbers have declined by about 30% over the past 10 years across Canada, and considerably more in Nova Scotia. A combination of factors, including loss of nesting habitat, reduced availability of insects, and threats encountered along the winter migration route and at overwintering areas in South America, have reduced the abundance of Bank swallows.

Bank Swallow recovery plan (PDF 12 MB)

Barn Swallow endangered

Hirundo rustica - 2013

Barn Swallows were one of the world`s most widespread species, but have undergone continental level declines across North America begining in the 1980s. Loss of important nesting sites in the wake of changing agricultural practices (barns) and other artificial structures such as bridges maybe implicated with declines. Concurrent declines of many other aerial insectivorous birds in Nova Scotia and throughout North America suggest changes in the insect food base and climate change may also be implicated. While actual mechanisms of the decline are not well understood the rapidity and geographic extent are cause for concern.

Barn Swallows were one of the world`s most widespread species, but have undergone continental level declines across North America begining in the 1980s. Loss of important nesting sites in the wake of changing agricultural practices (barns) and other artificial structures such as bridges maybe implicated with declines. Concurrent declines of many other aerial insectivorous birds in Nova Scotia and throughout North America suggest changes in the insect food base and climate change may also be implicated. While actual mechanisms of the decline are not well understood the rapidity and geographic extent are cause for concern.

Barn Swallow recovery plan (PDF 5 MB)

Bicknell's Thrush endangered

Catharus bicknelli - 2013

Bicknell's Thrush is endangered because of habitat change, low numbers, patchy distribution, and low reproductive potential. However, little is known about this secretive species. It breeds in Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and the northeastern United States. In Nova Scotia, it is currently restricted largely to Cape Breton Island, although historically it was found on a few offshore islands in the southwest part of the province. Habitat has been altered in Nova Scotia over the last century by infestations of spruce budworm and forest management

Bicknell's Thrush is endangered because of habitat change, low numbers, patchy distribution, and low reproductive potential. However, little is known about this secretive species. It breeds in Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and the northeastern United States. In Nova Scotia, it is currently restricted largely to Cape Breton Island, although historically it was found on a few offshore islands in the southwest part of the province. Habitat has been altered in Nova Scotia over the last century by infestations of spruce budworm and forest management

Bicknell's Thrush recovery plan (PDF 4 MB)

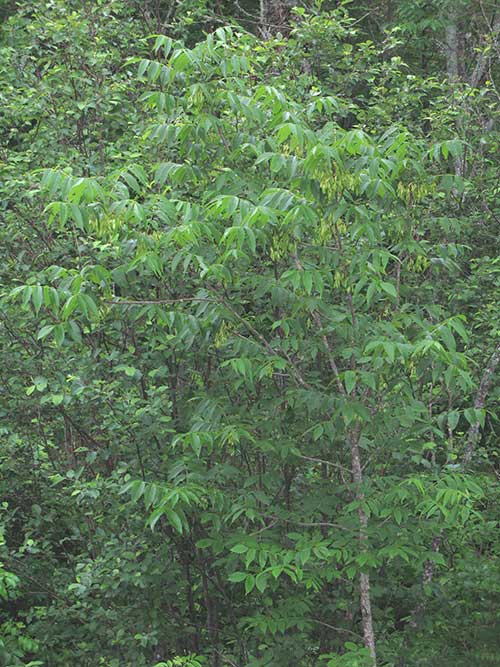

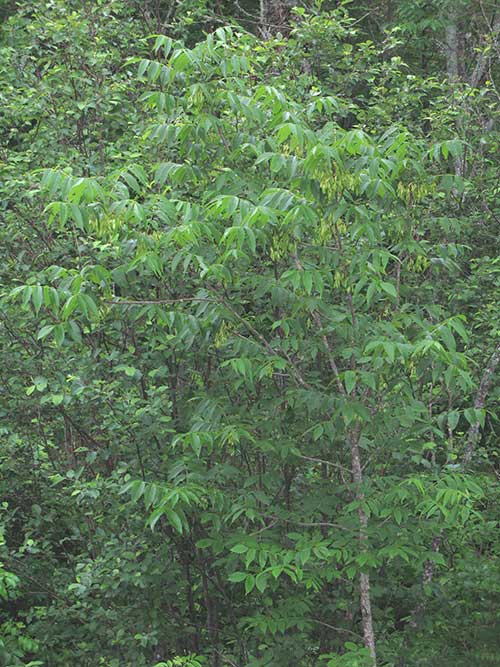

Black Ash threatened

Fraxinus nigra - 2013

Although Black Ash is Black ash is known from 35-40 sites in 11 counties of Nova Scotia mature individuals are rare and only 12 are known to occur. Total number of known trees in Nova Scotia is approximately 1000. Black ash are wind-pollinated and flower in late May or early June. Seeds are produced at 1 to 8 year intervals and are dispersed from October to the following spring. The number of seeds produced per tree ranges from 2 -1500. Seeds stay in dormancy between 2 to 8 years and seedlings are poor competitors. Black ash can sprout vigorously from stumps after cutting; most regeneration is occurs through this means. The species is slow growing, moderately long-lived with a typical longevity of 130 to 150 years. Black ash is particularly susceptible to fungal diseases, invasive species such as the Emerald Ash Borer, poor growth and stunting.

Although Black Ash is Black ash is known from 35-40 sites in 11 counties of Nova Scotia mature individuals are rare and only 12 are known to occur. Total number of known trees in Nova Scotia is approximately 1000. Black ash are wind-pollinated and flower in late May or early June. Seeds are produced at 1 to 8 year intervals and are dispersed from October to the following spring. The number of seeds produced per tree ranges from 2 -1500. Seeds stay in dormancy between 2 to 8 years and seedlings are poor competitors. Black ash can sprout vigorously from stumps after cutting; most regeneration is occurs through this means. The species is slow growing, moderately long-lived with a typical longevity of 130 to 150 years. Black ash is particularly susceptible to fungal diseases, invasive species such as the Emerald Ash Borer, poor growth and stunting.

Black Ash status report (PDF 691 kB)

Black Ash recovery plan (PDF 1 MB)

Black Ash core habitat (PDF 1 MB)

Black Foam Lichen threatened

Anzia colpodes - 2017

This leafy lichen grows on the trunks of mature deciduous trees – usually Red maple -- atop a dense thick spongy cushion of black fungal hairs. It is thought to historically occur only in eastern United States and Canada. The Canadian population -- representing 50% of the known global population -- appears restricted to only Nova Scotia. In Nova Scotia, the species is widely distributed, but uncommon. Forest harvesting, air pollution, climate change, and grazing by native and alien invasive slugs contribute to the loss and decline of Black foam lichen in the province.

This leafy lichen grows on the trunks of mature deciduous trees – usually Red maple -- atop a dense thick spongy cushion of black fungal hairs. It is thought to historically occur only in eastern United States and Canada. The Canadian population -- representing 50% of the known global population -- appears restricted to only Nova Scotia. In Nova Scotia, the species is widely distributed, but uncommon. Forest harvesting, air pollution, climate change, and grazing by native and alien invasive slugs contribute to the loss and decline of Black foam lichen in the province.

Black Foam Lichen recovery plan (PDF 2.7 MB)

Blanding's Turtle endangered

Emydoidea blandingii - 2000

Three small disjunct populations of Blanding's Turtle are found in central southwest Nova Scotia comprising around two hundred adult animals in total. These turtles are genetically distinct with behavioural and physical differences that distinguish them from Blanding's Turtles in Ontario and the United States. Predators like the raccoon and human alteration of lake shores (water level) used for nesting are the major threats to this species in Nova Scotia.

Three small disjunct populations of Blanding's Turtle are found in central southwest Nova Scotia comprising around two hundred adult animals in total. These turtles are genetically distinct with behavioural and physical differences that distinguish them from Blanding's Turtles in Ontario and the United States. Predators like the raccoon and human alteration of lake shores (water level) used for nesting are the major threats to this species in Nova Scotia.

Blanding's Turtle recovery plan (PDF 3 MB)

Blue Felt Lichen vulnerable

Pectenia plumbea - 2013

Blue Felt Lichen is known from 88 locations in Nova Scotia that represent a considerable portion of the entire range known in North America. Growing on the trunks of hardwood trees Blue Felt Lichen is threatened by activities that change the relative humidity in the forest and air born pollutants and acid rain that change the chemistry on the bark of trees. Forestry practices that do not adopt precaution to apply appropriate setbacks where the lichen occurs are considered a threat.

Blue Felt Lichen is known from 88 locations in Nova Scotia that represent a considerable portion of the entire range known in North America. Growing on the trunks of hardwood trees Blue Felt Lichen is threatened by activities that change the relative humidity in the forest and air born pollutants and acid rain that change the chemistry on the bark of trees. Forestry practices that do not adopt precaution to apply appropriate setbacks where the lichen occurs are considered a threat.

Blue Felt Lichen management plan 2025 (PDF 1 MB)

Bobolink vulnerable

Dolichonyx oryzivorus - 2013

Bobolinks are a bird of open grasslands and hayfields, habitats that in Nova Scotia were probably rare prior to settlement by Europeans. Boblinks have declined steadily over nearly three decades and are threatened by hay mowing that kills young and destroys nests. Other threats implicated with continent wide declines are poorly understood, but maybe implicated with loss of wintering habitat in the central United States and control programs for blackbirds within this area of their range.

Bobolinks are a bird of open grasslands and hayfields, habitats that in Nova Scotia were probably rare prior to settlement by Europeans. Boblinks have declined steadily over nearly three decades and are threatened by hay mowing that kills young and destroys nests. Other threats implicated with continent wide declines are poorly understood, but maybe implicated with loss of wintering habitat in the central United States and control programs for blackbirds within this area of their range.

Boreal Felt Lichen endangered

Erioderma pedicullatum - 2003

This small, inconspicuous lichen has experienced a dramatic decline of over 90% in occurrences and individuals over the last two decades. Boreal Felt Lichen is now known in Nova Scotia from only one site that includes three individuals all within an area of only a few hundred square meters. The primary threats to Boreal Felt Lichen are atmospheric pollutants and acid precipitation which can cause the death of individuals and disrupt reproduction. The lichen can also be threatened by forestry and other land use practices if they disrupt the moist microclimate that is essential for the species.

This small, inconspicuous lichen has experienced a dramatic decline of over 90% in occurrences and individuals over the last two decades. Boreal Felt Lichen is now known in Nova Scotia from only one site that includes three individuals all within an area of only a few hundred square meters. The primary threats to Boreal Felt Lichen are atmospheric pollutants and acid precipitation which can cause the death of individuals and disrupt reproduction. The lichen can also be threatened by forestry and other land use practices if they disrupt the moist microclimate that is essential for the species.

Boreal Felt Lichen recovery plan (PDF 15 MB)

Brook Floater threatened

Alasmidonta varicosa - 2013

Brook Floater is a fresh water mussel known from only 5 locations in Nova Scotia. Threats include alteration of shoreline for development, sedimentation, agricultural practices and changes in quality and quantity of water. Cumulative impacts from one or more of these sources may also be implicated with loss of populations.

Brook Floater is a fresh water mussel known from only 5 locations in Nova Scotia. Threats include alteration of shoreline for development, sedimentation, agricultural practices and changes in quality and quantity of water. Cumulative impacts from one or more of these sources may also be implicated with loss of populations.

Brook Floater recovery plan (PDF 5 MB)

Canada Lynx endangered

Lynx canadensis - 2002

Lynx formerly occurred in areas of suitable habitat across mainland Nova Scotia and Cape Breton Island. The current population is very small and restricted to two areas in the highlands of Cape Breton Island. Historic and current threats to Lynx include: harvesting, competition from bobcats and coyotes, habitat loss, disease and climate change.

Lynx formerly occurred in areas of suitable habitat across mainland Nova Scotia and Cape Breton Island. The current population is very small and restricted to two areas in the highlands of Cape Breton Island. Historic and current threats to Lynx include: harvesting, competition from bobcats and coyotes, habitat loss, disease and climate change.

Canada Lynx recovery plan 2025 (PDF 1 MB)

Canada Lynx status report (PDF 918 kB)

Canada Lynx recovery plan 2007 (PDF 276 kB)

Canada Warbler endangered

Cardellina canadensis - 2013

About 80% of the breeding range of this neotropical migrant is in Canada and significant declines have been continuing for nearly three decades. Although factors affecting declines of Canada Warbler are not well understood, loss of wintering habitat in South America and climate change may be implicated. Canada Warblers utilize wetlands, swamps, bogs and fens in forest habitats for nesting. (click image for larger picture.)

About 80% of the breeding range of this neotropical migrant is in Canada and significant declines have been continuing for nearly three decades. Although factors affecting declines of Canada Warbler are not well understood, loss of wintering habitat in South America and climate change may be implicated. Canada Warblers utilize wetlands, swamps, bogs and fens in forest habitats for nesting. (click image for larger picture.)

Canada Warbler recovery plan (PDF 1 MB)

Chimney Swift endangered

Chaetura pelagica - 2007

The Canadian population of Chimney swift has declined by almost 30 percent in the past 13 years and geographic area these birds occupy has declined about one third over the same period. In Nova Scotia,the number and the sites where chimney swifts are found has also declined. Many aerial insect eating bird species have declined throughout the Americas in the past 30 years. The cause of the declines is not clear but likely involves changes in insect populations due to habitat changes and pesticide use. A decline in chimneys and large hollow tress that are used for nesting and roosting is also a factor. Large kills resulting from hurricanes crossing migration paths has recently been a serious concern.

The Canadian population of Chimney swift has declined by almost 30 percent in the past 13 years and geographic area these birds occupy has declined about one third over the same period. In Nova Scotia,the number and the sites where chimney swifts are found has also declined. Many aerial insect eating bird species have declined throughout the Americas in the past 30 years. The cause of the declines is not clear but likely involves changes in insect populations due to habitat changes and pesticide use. A decline in chimneys and large hollow tress that are used for nesting and roosting is also a factor. Large kills resulting from hurricanes crossing migration paths has recently been a serious concern.

Chimney Swift recovery plan (PDF 6 MB)

Common Nighthawk threatened

Chordeiles minor - 2007

In Canada, this species has shown both long and short-term declines in population. Over the last nine years, a 49 percent decline was observed in survey. Declines have also been observed in Nova Scotia. Reduction in insect food resources has apparently contributed to the decline of this species as with other aerial insectivore. Reduction in habitat availability caused by fire suppression, intensive agriculture and declines in gravel rooftops in urban areas, may also be factors in some regions.

In Canada, this species has shown both long and short-term declines in population. Over the last nine years, a 49 percent decline was observed in survey. Declines have also been observed in Nova Scotia. Reduction in insect food resources has apparently contributed to the decline of this species as with other aerial insectivore. Reduction in habitat availability caused by fire suppression, intensive agriculture and declines in gravel rooftops in urban areas, may also be factors in some regions.

Common Nighthawk recovery plan (PDF 863 kB)

Eastern Baccharis threatened

Baccharis hamilifolia - 2013

Eastern Baccaharis is a large perennial shrub that has male and female flowers on different plants. It grows in btween the upper edge of the saltmarsh and the forested upland. Nova Scotia's small population is disjunct, unique in Canada and the nearest populations elsewhere are located in Massachusetts. Two small populations exist in Nova Scotia comprised of about 2800 plants. The primary threat is climate change tied to rising sea levels, storm surge and shore alteration.

Eastern Baccaharis is a large perennial shrub that has male and female flowers on different plants. It grows in btween the upper edge of the saltmarsh and the forested upland. Nova Scotia's small population is disjunct, unique in Canada and the nearest populations elsewhere are located in Massachusetts. Two small populations exist in Nova Scotia comprised of about 2800 plants. The primary threat is climate change tied to rising sea levels, storm surge and shore alteration.

Eastern Baccharis recovery plan (PDF 3 MB)

Eastern Lilaeopsis vulnerable

Lilaeopsis chinensis - 2006

Lilaeopsis is a small perennial herb reproducing both by seed and extensively by vegetative spread. It is highly restricted geographically and present in Canada at only three estuaries in Nova Scotia. Despite this, the population is large. No declines of significance have been documented over the last 15 years. It does not appear to have any imminent threats; however, future shoreline development or degradation could destroy extant populations.

Lilaeopsis is a small perennial herb reproducing both by seed and extensively by vegetative spread. It is highly restricted geographically and present in Canada at only three estuaries in Nova Scotia. Despite this, the population is large. No declines of significance have been documented over the last 15 years. It does not appear to have any imminent threats; however, future shoreline development or degradation could destroy extant populations.

Eastern Mountain Avens endangered

Geum peckii - 2000

This highly disjunct plant species is found in Canada at only six sites in Digby Neck and Brier Island. At some sites the populations have declined substantially or have disappeared altogether. This is due to habitat loss and degradation caused by the draining of wetlands and the invasion of habitat by weeds and shrubs. These invasions may be the result of nutrient enrichment by large populations of Herring and Greater black-backed Gulls.

This highly disjunct plant species is found in Canada at only six sites in Digby Neck and Brier Island. At some sites the populations have declined substantially or have disappeared altogether. This is due to habitat loss and degradation caused by the draining of wetlands and the invasion of habitat by weeds and shrubs. These invasions may be the result of nutrient enrichment by large populations of Herring and Greater black-backed Gulls.

Eastern Mountain Avens recovery plan (PDF 1 MB)

Eastern Ribbonsnake threatened

Thamnophis sauritus - 2003

In Nova Scotia, the Ribbon Snake exists as a small, isolated post-glacial relic population confined to the southwest part of the province. This semi-aquatic snake is restricted to specialized habitats on lakeshores and other wetland habitats. Little is known about the species. As such, it is unique and due to its apparently small population is susceptible to demographic and environmental fluctuations. In addition, the species is threatened by habitat loss due to shoreline development.

In Nova Scotia, the Ribbon Snake exists as a small, isolated post-glacial relic population confined to the southwest part of the province. This semi-aquatic snake is restricted to specialized habitats on lakeshores and other wetland habitats. Little is known about the species. As such, it is unique and due to its apparently small population is susceptible to demographic and environmental fluctuations. In addition, the species is threatened by habitat loss due to shoreline development.

Eastern Ribbonsnake recovery plan (PDF 3 MB)

Eastern Waterfan threatened

Peltigera hydrothyria - 2017

Eastern water fan is an unusual aquatic leafy lichen that colonizes specific types of clear mineral-enriched streams at or below water level. Colonies attach to stones or tree branches. In North America, it is known for restricted parts of eastern United States and Canada. About 25% of the known global population occurs in Canada; six of the ten known occurrences in Canada are in Nova Scotia. There is little historical data for the species, but Eastern water fan appears to have always been uncommon. Activities that alter water quality -- including temperature, clarity, flow, levels, and acidity – pose a threat to Eastern water fan. Deforestation, soil erosion, air pollution, and climate change can harm the general habitat and immediate microhabitat of this species.

Eastern water fan is an unusual aquatic leafy lichen that colonizes specific types of clear mineral-enriched streams at or below water level. Colonies attach to stones or tree branches. In North America, it is known for restricted parts of eastern United States and Canada. About 25% of the known global population occurs in Canada; six of the ten known occurrences in Canada are in Nova Scotia. There is little historical data for the species, but Eastern water fan appears to have always been uncommon. Activities that alter water quality -- including temperature, clarity, flow, levels, and acidity – pose a threat to Eastern water fan. Deforestation, soil erosion, air pollution, and climate change can harm the general habitat and immediate microhabitat of this species.

Eastern Waterfan recovery plan (PDF 4 MB)

Eastern Whip-poor-will threatened

Antrostomus vociferus - 2013

Whip-poor-will have always been a rare breeding bird in Nova Scotia at the most northern extent of their range in North America. Declines of 30% or more in Canada over the last decade and increasing unpredictability (stochastic) of breeding locations in Nova Scotia are cause for concern. Feeding exclusively on aerial insects, Whip-poor-wills nest in open forests, glades or abandoned roads often near water. Habitat loss in the breeding grounds and wintering grounds in South America are thought to be major threats. Changes in the insect prey base and climate change may also be implicated.

Whip-poor-will have always been a rare breeding bird in Nova Scotia at the most northern extent of their range in North America. Declines of 30% or more in Canada over the last decade and increasing unpredictability (stochastic) of breeding locations in Nova Scotia are cause for concern. Feeding exclusively on aerial insects, Whip-poor-wills nest in open forests, glades or abandoned roads often near water. Habitat loss in the breeding grounds and wintering grounds in South America are thought to be major threats. Changes in the insect prey base and climate change may also be implicated.

Eastern Whip-poor-will recovery plan (PDF 4 MB)

Eastern White Cedar vulnerable

Thuja occidentalis - 2006

Cedar is an uncommon tree in Nova Scotia and currently only 32 stands in five counties have been identified. The population is fragmented and comprised of mostly small stands that appear genetically separate from each. Most populations are different from populations in NB and PEI. Almost all of the cedar are located on private land and only one stand is formally protected. In the recent past stands have been lost to forest harvesting and highway construction. Ornamental cedars of the same species have been planted around homes and in gardens; these trees are not considered part of the native population and are not covered by the listing under the Act.

Cedar is an uncommon tree in Nova Scotia and currently only 32 stands in five counties have been identified. The population is fragmented and comprised of mostly small stands that appear genetically separate from each. Most populations are different from populations in NB and PEI. Almost all of the cedar are located on private land and only one stand is formally protected. In the recent past stands have been lost to forest harvesting and highway construction. Ornamental cedars of the same species have been planted around homes and in gardens; these trees are not considered part of the native population and are not covered by the listing under the Act.

Eastern White Cedar status report (PDF 264 kB)

Eastern White Cedar management plan (PDF 935 kB)

Eastern Wood Pewee vulnerable

Contopus virens - 2013

Eastern Wood Pewee are one of the most characteristic birds of woodlands in eastern North America, but have suffered ongoing declines over nearly four decades. Feeding almost exclusively on small flying insects, this small flycatcher nests high out on a forked limb finishing its nest with bits of lichen for camouflage. Causes of the declining numbers of Eastern Wood Pewee are unclear, but are thought to be implicated with loss of habitat in the wintering range in South America, forest practices in Canada, climate change and other factors.

Eastern Wood Pewee are one of the most characteristic birds of woodlands in eastern North America, but have suffered ongoing declines over nearly four decades. Feeding almost exclusively on small flying insects, this small flycatcher nests high out on a forked limb finishing its nest with bits of lichen for camouflage. Causes of the declining numbers of Eastern Wood Pewee are unclear, but are thought to be implicated with loss of habitat in the wintering range in South America, forest practices in Canada, climate change and other factors.

Eastern Wood Pewee management plan (PDF 1 MB)

Evening Grosbeak vulnerable

Coccothraustes vespertinus - 2017

The Evening grosbeak is a large chunky social finch with a thick bill, bright distinctive coloration, and noisy call. A flocking bird, it forages in treetops and branches for insects, seeds and berries and is a frequent visitor to winter feeders. It lives in mature mixed and softwood boreal forest. Evening grosbeak has exhibited marked long-term decline throughout most of its range over the past 20 years. The cause of the decline of Evening grosbeak is unknown. Habitat loss in its boreal breeding areas and climate change may be contributing to the long term downward trend.

The Evening grosbeak is a large chunky social finch with a thick bill, bright distinctive coloration, and noisy call. A flocking bird, it forages in treetops and branches for insects, seeds and berries and is a frequent visitor to winter feeders. It lives in mature mixed and softwood boreal forest. Evening grosbeak has exhibited marked long-term decline throughout most of its range over the past 20 years. The cause of the decline of Evening grosbeak is unknown. Habitat loss in its boreal breeding areas and climate change may be contributing to the long term downward trend.

Golden-crest vulnerable

Lophiola aurea - 2013

An Atlantic Coastal Plain species of plant found in a six wetlands in southwestern Nova Scotia. These are the only locations for this plant in Canada. Historically, two populations were lost and the extant populations are all under some threat. Threats include alteration of wetland and shoreline habitat through land use change, water level manipulation and eutrophication (nutrient enrichment). (click image for larger pictures)

An Atlantic Coastal Plain species of plant found in a six wetlands in southwestern Nova Scotia. These are the only locations for this plant in Canada. Historically, two populations were lost and the extant populations are all under some threat. Threats include alteration of wetland and shoreline habitat through land use change, water level manipulation and eutrophication (nutrient enrichment). (click image for larger pictures)

Gypsy Cuckoo Bumble Bee endangered

Bombus bohemicus - 2017

The Gypsy cuckoo bumble bee is a nest parasite of other bumble bees. It invades other bee nests, displaces the resident queen and enslaves the resident workers. This large distinctive bee occurs widely across Canada. Although never abundant, the species distribution is shrinking and is thought to have disappeared from Nova Scotia in the last 20 years. Reasons for the decline are linked to the decline of host bumble bee species, pesticide use, competition from non-native bees, introduction of pathogens by alien bee species, and the expanding urbanization of natural landscapes.

The Gypsy cuckoo bumble bee is a nest parasite of other bumble bees. It invades other bee nests, displaces the resident queen and enslaves the resident workers. This large distinctive bee occurs widely across Canada. Although never abundant, the species distribution is shrinking and is thought to have disappeared from Nova Scotia in the last 20 years. Reasons for the decline are linked to the decline of host bumble bee species, pesticide use, competition from non-native bees, introduction of pathogens by alien bee species, and the expanding urbanization of natural landscapes.

Gypsy cuckoo bumble bee recovery plan (PDF 10 MB)

Harlequin Duck endangered

Historonicus historonicus - 2000

Less than 250 Harlequin Ducks winter on the coast of Nova Scotia. The eastern sub-species, which occurs here, has declined. Little is known about it other than that it breeds along rivers in Labrador and Newfoundland. This species is at risk because of its small population size and other factors including illegal hunting and oil spills.

Less than 250 Harlequin Ducks winter on the coast of Nova Scotia. The eastern sub-species, which occurs here, has declined. Little is known about it other than that it breeds along rivers in Labrador and Newfoundland. This species is at risk because of its small population size and other factors including illegal hunting and oil spills.

Hoary Willow endangered

Salix candida - 2013

In Nova Scotia, Hoary Willow occurs only within the Black River system at the northwest end of Lake Ainslie, Inverness County, Cape Breton Island. Here it is known from four rich calcareous fens in close proximity to the river floodplain and a marsh. Threats include hydrologic alteration, grazing, browsing, recreational use, alteration of natural fire regime, invasive species and timber harvesting. Peat mining could also pose a serious threat to the provincial population.

In Nova Scotia, Hoary Willow occurs only within the Black River system at the northwest end of Lake Ainslie, Inverness County, Cape Breton Island. Here it is known from four rich calcareous fens in close proximity to the river floodplain and a marsh. Threats include hydrologic alteration, grazing, browsing, recreational use, alteration of natural fire regime, invasive species and timber harvesting. Peat mining could also pose a serious threat to the provincial population.

Hoary Willow recovery plan (PDF 2 MB)

Little Brown Myotis endangered

Myotis lucifugus - 2013

What was once the most common bat in Nova Scotia is now endangered by a disease known as White-nose-Syndrome caused by the fungus, Pseudogymnoascus destructans . The disease has killed nearly 7 million bats in eastern North America in the past 8 years and estimates of a 90% percent decline in Nova Scotia have taken place in just 3 years since the disease was first recorded. There is no known cure for the disease which is lethal and affects all bat species that congregate in caves and abandoned mines used for hibernation through the winter. About 16 hibernation sites are known in Nova Scotia.

What was once the most common bat in Nova Scotia is now endangered by a disease known as White-nose-Syndrome caused by the fungus, Pseudogymnoascus destructans . The disease has killed nearly 7 million bats in eastern North America in the past 8 years and estimates of a 90% percent decline in Nova Scotia have taken place in just 3 years since the disease was first recorded. There is no known cure for the disease which is lethal and affects all bat species that congregate in caves and abandoned mines used for hibernation through the winter. About 16 hibernation sites are known in Nova Scotia.

Little Brown Myotis recovery plan (PDF 19 MB)

Long's Bulrush vulnerable

Scirpus longii - 2001

An Atlantic Coastal Plain species in Canada known from ten sites in Nova Scotia. It is a very long-lived plant that forms conspicuous circular clones. It inhabits bogs and other wetlands. The populations have been impacted by wetland modification in the past and would be susceptible to wetland development in the future.

An Atlantic Coastal Plain species in Canada known from ten sites in Nova Scotia. It is a very long-lived plant that forms conspicuous circular clones. It inhabits bogs and other wetlands. The populations have been impacted by wetland modification in the past and would be susceptible to wetland development in the future.

Macropis Cuckoo Bee endangered

Epeoloides pilosulus - 2013

Macropis Cuckoo Bee was historically known from 5 Canadian provinces but disappeared from the record for decades until one site was located in the Annapolis Valley a few years ago. Despite vigorous inventory the cuckoo bee has not been relocated at this site suggesting that the species is in imminent threat of extinction, or extirpation, in the province and perhaps North America. The decline of this bee is not well understood, but habitat loss, and use of insecticides are considered major threats.

Macropis Cuckoo Bee was historically known from 5 Canadian provinces but disappeared from the record for decades until one site was located in the Annapolis Valley a few years ago. Despite vigorous inventory the cuckoo bee has not been relocated at this site suggesting that the species is in imminent threat of extinction, or extirpation, in the province and perhaps North America. The decline of this bee is not well understood, but habitat loss, and use of insecticides are considered major threats.

Macropis Cuckoo Bee (PDF 937 kB)

Monarch endangered

Danaus plexippus - 2017

The showy Monarch butterfly – one of the world’s recognizable insects – has experienced a 90% decrease since the 1990s. It faces multiple threats most notably disruption of unique forested mountain areas in Mexico where most of the global population overwinters, and habitat loss in summer breeding areas in Canada and the United States. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) recognizes the migration of Monarch butterfly as a ‘threatened process.’ Recovery of the species requires conservation effort throughout its range. The increased use of industrial herbicides in North America has depleted habitat for breeding Monarch butterflies. Native Swamp milkweed and the introduced Common milkweed are essential adult breeding habitat and larval food sources in Nova Scotia.

The showy Monarch butterfly – one of the world’s recognizable insects – has experienced a 90% decrease since the 1990s. It faces multiple threats most notably disruption of unique forested mountain areas in Mexico where most of the global population overwinters, and habitat loss in summer breeding areas in Canada and the United States. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) recognizes the migration of Monarch butterfly as a ‘threatened process.’ Recovery of the species requires conservation effort throughout its range. The increased use of industrial herbicides in North America has depleted habitat for breeding Monarch butterflies. Native Swamp milkweed and the introduced Common milkweed are essential adult breeding habitat and larval food sources in Nova Scotia.

Monarch recovery plan (PDF 1 MB)

Moose (Mainland Population) endangered

Alces alces americana - 2003

The native population of moose in Nova Scotia is limited to approximately 1000 individuals in isolated sub-populations across the mainland. The population has declined by at least 20% over the past 30 years with much greater reductions in distribution and population size over more than 200 years, despite emxtensive hunting closures since the 1930's. The decline is not well understood but involves a complex of threats including: over harvesting, illegal hunting, climate change, parasitic brainworm, increased road access to moose habitat, spread of white-tailed deer, very high levels of cadmium, deficiencies in cobalt and possibly an unknown viral disease.

The native population of moose in Nova Scotia is limited to approximately 1000 individuals in isolated sub-populations across the mainland. The population has declined by at least 20% over the past 30 years with much greater reductions in distribution and population size over more than 200 years, despite emxtensive hunting closures since the 1930's. The decline is not well understood but involves a complex of threats including: over harvesting, illegal hunting, climate change, parasitic brainworm, increased road access to moose habitat, spread of white-tailed deer, very high levels of cadmium, deficiencies in cobalt and possibly an unknown viral disease.

Mainland Moose status report (PDF 973 kB)

Mainland Moose recovery plan (PDF 4 MB)

Mainland Moose action plan (PDF 1 MB)

Moose on Cape Breton Island are not risk as they are abundant and the result of a re-introduction of moose from Alberta in the 1940's.

New Jersey Rush vulnerable

Juncus caesariensis - 2006

An Atlantic Coastal Plain species in Canada known only from sixteen bogs and fens in south eastern Cape Breton. The species grows on the edge of bogs and fens. It is locally abundant in some sites and Nova Scotia supports over fifty percent of the world's population. Land use activities that disrupt the integrity of the edge of these bogs could compromise the survival of this species.

An Atlantic Coastal Plain species in Canada known only from sixteen bogs and fens in south eastern Cape Breton. The species grows on the edge of bogs and fens. It is locally abundant in some sites and Nova Scotia supports over fifty percent of the world's population. Land use activities that disrupt the integrity of the edge of these bogs could compromise the survival of this species.

Northern Myotis endangered

Myotis septentrionalis - 2013

The Northern Myotis, or Northern Long-eared bat is the second most common bat in the province. It usually hibernates in association with the Little Brown Bat in caves and abandoned mines and at other times of the year is a true forest bat. Northern Myotis are endangered by a disease known as White-nose-Syndrome caused by the fungus, Geomyces destructans. There is no known cure for the disease which is lethal and affects all bat species that congregate in caves and abandoned mines used for hibernation through the winter. Like the Little Brown Bat, the Northern Myotis can live to be 15 or more years of age, but they have low fecundity, and high mortality of juveniles, all of which pose significant threats to their recovery.

The Northern Myotis, or Northern Long-eared bat is the second most common bat in the province. It usually hibernates in association with the Little Brown Bat in caves and abandoned mines and at other times of the year is a true forest bat. Northern Myotis are endangered by a disease known as White-nose-Syndrome caused by the fungus, Geomyces destructans. There is no known cure for the disease which is lethal and affects all bat species that congregate in caves and abandoned mines used for hibernation through the winter. Like the Little Brown Bat, the Northern Myotis can live to be 15 or more years of age, but they have low fecundity, and high mortality of juveniles, all of which pose significant threats to their recovery.

Northern Myotis recovery plan (PDF 19 MB)

Olive-sided Flycatcher threatened

Contopus cooperi - 2013

Olive-sided Flyactcher are one of the most characteristic birds of spruce and fir swamps and bogs with open water in Nova Scotia. The plaintive call can be heard from great distance that many transcribe as `Quick Three Beer!` Long-term declines of 79% across Canada have been punctuated by more recent declines of 29% between 1996-2006. Habitat loss in the wintering grounds, changes in the insect food base and climate change are all factors implicated with the decrease in Olive-sided Flycatchers.

Olive-sided Flyactcher are one of the most characteristic birds of spruce and fir swamps and bogs with open water in Nova Scotia. The plaintive call can be heard from great distance that many transcribe as `Quick Three Beer!` Long-term declines of 79% across Canada have been punctuated by more recent declines of 29% between 1996-2006. Habitat loss in the wintering grounds, changes in the insect food base and climate change are all factors implicated with the decrease in Olive-sided Flycatchers.

Olive-sided Flycatcher recovery plan (PDF 1 MB)

Peregrine Falcon vulnerable

Falco perigrinus anatum - 2007

Continental populations of Peregrine Falcon have shown continuing increases in population size since the 1970's up to near historical numbers. In Nova Scotia, the species has recovered in the Bay of Fundy area and numbers nesting may exceed historical levels. This recovery has been the result of reintroductions across much of Southern Canada, and natural increases in productivity following the ban in Canada of organochlorine pesticides (e.g. DDT). These compounds were the primary factor responsible for the historic decline and continue to be found in peregrine tissues, but at levels that do not significantly affect reproductive success. The unknown effects of new pesticides regularly licensed for use in Canada are also a concern.

Continental populations of Peregrine Falcon have shown continuing increases in population size since the 1970's up to near historical numbers. In Nova Scotia, the species has recovered in the Bay of Fundy area and numbers nesting may exceed historical levels. This recovery has been the result of reintroductions across much of Southern Canada, and natural increases in productivity following the ban in Canada of organochlorine pesticides (e.g. DDT). These compounds were the primary factor responsible for the historic decline and continue to be found in peregrine tissues, but at levels that do not significantly affect reproductive success. The unknown effects of new pesticides regularly licensed for use in Canada are also a concern.

Pink Coreopsis endangered

Coreopsis rosea - 2000

This Atlantic Coastal Plain plant species is found in Canada on the shores of only three lakes in Nova Scotia. Populations in the United States are also at risk. Threats include: human alteration and loss of lakeshore habitats, water pollution, destruction of populations and habitat by ATV's and other recreational activities.

This Atlantic Coastal Plain plant species is found in Canada on the shores of only three lakes in Nova Scotia. Populations in the United States are also at risk. Threats include: human alteration and loss of lakeshore habitats, water pollution, destruction of populations and habitat by ATV's and other recreational activities.

Pink Coreopsis recovery plan (PDF 3 MB)

Piping Plover endangered

Charadrius melodius - 2000

In Nova Scotia only about forty breeding pairs of Piping Plovers remain. These birds are dispersed around the province on seventeen sand beaches. Despite concerted conservation efforts here and elsewhere in North America, the numbers of this species remain low. The main reasons for this include: deterioration of marginal nesting habitat due to natural events (storms, vegetation succession), human alteration of beach habitat, human disturbance during nesting and predation by birds and mammals on eggs and young.(click image for larger pictures.)

In Nova Scotia only about forty breeding pairs of Piping Plovers remain. These birds are dispersed around the province on seventeen sand beaches. Despite concerted conservation efforts here and elsewhere in North America, the numbers of this species remain low. The main reasons for this include: deterioration of marginal nesting habitat due to natural events (storms, vegetation succession), human alteration of beach habitat, human disturbance during nesting and predation by birds and mammals on eggs and young.(click image for larger pictures.)

Piping Plover recovery plan (PDF 5 MB)

Plymouth Gentian endangered

Sabatia kennedyana - 2013

An Atlantic Coastal Plain species, known in Canada only from a small number of lakeshores in Nova Scotia. The populations here are very small. Threats include: human alteration and loss of lakeshore habitats, water pollution, destruction of populations and habitat by ATV's and other recreational activities.(click image for larger picture.)

An Atlantic Coastal Plain species, known in Canada only from a small number of lakeshores in Nova Scotia. The populations here are very small. Threats include: human alteration and loss of lakeshore habitats, water pollution, destruction of populations and habitat by ATV's and other recreational activities.(click image for larger picture.)

Plymouth Gentian recovery plan (PDF 3 MB)

Prototype Quillwort vulnerable

Isoetes prototypes - 2006

A regional endemic with almost all of its global population in Canada . The species is an aquatic perennial with very specific habitat requirements limiting its occurrence in Canada to about 12 small unconnected lakes, 9 of which are in Nova Scotia. The species is found in nutrient-poor, cold, spring-fed lakes. Although several sites have been shown to contain large numbers of plants, one half of the documented sites contain small populations. A wide range of potential limiting factors could impact the species, including changes in water quality, boating and shoreline development.

A regional endemic with almost all of its global population in Canada . The species is an aquatic perennial with very specific habitat requirements limiting its occurrence in Canada to about 12 small unconnected lakes, 9 of which are in Nova Scotia. The species is found in nutrient-poor, cold, spring-fed lakes. Although several sites have been shown to contain large numbers of plants, one half of the documented sites contain small populations. A wide range of potential limiting factors could impact the species, including changes in water quality, boating and shoreline development.

Prototype Quillwort recovery plan (PDF 737 kB)

Ram's-Head Lady Slipper endangered

Cypripedium arietinum - 2007

Ram's-head Lady Slipper is a small, herbaceous, perennial, orchid of open forests. In Nova Scotia, this orchid is associated with gypsum bedrock and it is found only at six locations with only two to 500 individuals at each site. The species is at some level of risk over much of its range in Canada and Northeastern United States. Although numbers in the province appear stable at present, over the past 75 years, there has been considerable loss of habitat due to gypsum mining and other types of land conversion. Demonstrated threats to this species include; gypsum mining, forestry and cattle grazing. Competition with exotic species, housing developments and ATV traffic are potential local threats.

Ram's-head Lady Slipper is a small, herbaceous, perennial, orchid of open forests. In Nova Scotia, this orchid is associated with gypsum bedrock and it is found only at six locations with only two to 500 individuals at each site. The species is at some level of risk over much of its range in Canada and Northeastern United States. Although numbers in the province appear stable at present, over the past 75 years, there has been considerable loss of habitat due to gypsum mining and other types of land conversion. Demonstrated threats to this species include; gypsum mining, forestry and cattle grazing. Competition with exotic species, housing developments and ATV traffic are potential local threats.

Ram's-Head Lady Slipper status report (PDF 324 kB)

Ram's-Head Lady Slipper recovery plan (PDF 1 MB)

Red Knot endangered

Calidris canutus rufa subspecies - 2007

This medium sized shorebird subspecies breeds in arctic Canada and migrates thousands of kilometres between the breeding grounds and wintering areas in south America. This subspecies of Red Knot has shown a 70 percent decline in population size over the past 15 years. In Nova Scotia, Red Knot stopover to feed during their migration south in late summer. Counts and surveys in the province also show a decline. The primary cause of the decline is considered to be the depletion of horseshoe crabs. These crab eggs are a critical food source during the spring migration north.

This medium sized shorebird subspecies breeds in arctic Canada and migrates thousands of kilometres between the breeding grounds and wintering areas in south America. This subspecies of Red Knot has shown a 70 percent decline in population size over the past 15 years. In Nova Scotia, Red Knot stopover to feed during their migration south in late summer. Counts and surveys in the province also show a decline. The primary cause of the decline is considered to be the depletion of horseshoe crabs. These crab eggs are a critical food source during the spring migration north.

Red Knot recovery plan (PDF 3 MB)

Redroot vulnerable

Lachnanthes caroliana - 2013

An Atlantic Coastal Plain species, known in Canada only from a small number of lakeshores in Nova Scotia. The populations are small and very restricted in distribution. Threats to the species include; human alteration and loss of lakeshore habitats, water pollution, destruction of populations and habitat by ATV's and other recreational activities.

An Atlantic Coastal Plain species, known in Canada only from a small number of lakeshores in Nova Scotia. The populations are small and very restricted in distribution. Threats to the species include; human alteration and loss of lakeshore habitats, water pollution, destruction of populations and habitat by ATV's and other recreational activities.

Rockrose (Canada Frostweed) endangered

Helianthumum canadense - 2007

Rockrose is a perennial herb with showy yellow flowers and in Nova Scotia is generally associated with the dry, sandy Corema barrens (heathland) of the Annapolis Valley. Only about 3% of these barrens remain. Currently there are about 5500 mature Rockrose plants at seven sites. Nova Scotia plants are to some extent genetically unique and different from the nearest populations in Quebec and New England. Threats to Rockrose include the historic and ongoing land use change: agriculture, housing development, sand quarrying and other forms of development. Also, changes in the natural disturbances including suppression of fire, loss of caribou (grazing suppressing competition) and invasive Scots Pine (shading) have altered the habitat for rockrose.

Rockrose is a perennial herb with showy yellow flowers and in Nova Scotia is generally associated with the dry, sandy Corema barrens (heathland) of the Annapolis Valley. Only about 3% of these barrens remain. Currently there are about 5500 mature Rockrose plants at seven sites. Nova Scotia plants are to some extent genetically unique and different from the nearest populations in Quebec and New England. Threats to Rockrose include the historic and ongoing land use change: agriculture, housing development, sand quarrying and other forms of development. Also, changes in the natural disturbances including suppression of fire, loss of caribou (grazing suppressing competition) and invasive Scots Pine (shading) have altered the habitat for rockrose.

Rockrose (Canada Frostweed) recovery plan (PDF 3 MB)

Roseate Tern endangered

Sterna dougallii - 2000

About one hundred pairs of this seabird breed in Canada. All but a few pairs are in a small number of colonies in Nova Scotia. The size of the population and the number of breeding sites have declined markedly in the past fifty years. Predation by gulls on eggs and young, human disturbance at colonies and coastal development all pose significant threats to this species.

About one hundred pairs of this seabird breed in Canada. All but a few pairs are in a small number of colonies in Nova Scotia. The size of the population and the number of breeding sites have declined markedly in the past fifty years. Predation by gulls on eggs and young, human disturbance at colonies and coastal development all pose significant threats to this species.

Roseate Tern recovery plan (PDF 1 MB)

Rusty Blackbird endangered

Euphagus carolinus - 2013

Rusty Blackbirds utilize wetlands around lake edges, bogs, swamps and edges of fens for breeding, wintering in the central parts of the United States. Slow, steady long-term declines spanning over three decades have resulted in the listing of this species as Endangered. Factors affecting the decline are unclear, however habitat changes and blackbird control programs in agricultural landscapes in the wintering grounds are believed to be major threats. About 70% of the breeding range of Rusty Blackbirds is in Canada.

Rusty Blackbirds utilize wetlands around lake edges, bogs, swamps and edges of fens for breeding, wintering in the central parts of the United States. Slow, steady long-term declines spanning over three decades have resulted in the listing of this species as Endangered. Factors affecting the decline are unclear, however habitat changes and blackbird control programs in agricultural landscapes in the wintering grounds are believed to be major threats. About 70% of the breeding range of Rusty Blackbirds is in Canada.

Sable Island Sweat Bee threatened

Lasioglossum sablense - 2017

Sable Island Nova Scotia is the only known location on the planet for the aptly named Sable Island sweat bee. Very little is known about the ecology or population trend of this ground nesting bee species, given its rarity and exceptionally localized, remote distribution. Of the four bee species present on Sable Island, this species is the least common. Sable Island sweat bee appears to be generalist, able to use a variety of flowering plants for pollen and nectar, and tends to range within close proximity of its nest site. Threats to this species include the introduction of invasive species (including other bees and plants), bee-attacking insects, and catastrophic weather events. The populations’ highly restricted global distribution renders the species’ survival vulnerable to single-event physical disturbances.

Sable Island Nova Scotia is the only known location on the planet for the aptly named Sable Island sweat bee. Very little is known about the ecology or population trend of this ground nesting bee species, given its rarity and exceptionally localized, remote distribution. Of the four bee species present on Sable Island, this species is the least common. Sable Island sweat bee appears to be generalist, able to use a variety of flowering plants for pollen and nectar, and tends to range within close proximity of its nest site. Threats to this species include the introduction of invasive species (including other bees and plants), bee-attacking insects, and catastrophic weather events. The populations’ highly restricted global distribution renders the species’ survival vulnerable to single-event physical disturbances.

Sable Island Sweat Bee recovery plan (PDF 1 MB)

Snapping Turtle vulnerable

Chelydra serpentina - 2013

While snapping turtles remain fairly common in most watersheds in Nova Scotia, populations are under increasing threats. Low recruitment of turtles to breed, high juvenile mortality, nest failures exacerbated by turtles nesting in highly disturbed environments (road edges, quarries), illegal harvest and road mortality all are threats to the province's largest terrestrial/freshwater turtle. Studies from elsewhere in North America suggest that adults can live to be 100 years old. Any activity that causes adult mortality poses an elevated risk to this species.

While snapping turtles remain fairly common in most watersheds in Nova Scotia, populations are under increasing threats. Low recruitment of turtles to breed, high juvenile mortality, nest failures exacerbated by turtles nesting in highly disturbed environments (road edges, quarries), illegal harvest and road mortality all are threats to the province's largest terrestrial/freshwater turtle. Studies from elsewhere in North America suggest that adults can live to be 100 years old. Any activity that causes adult mortality poses an elevated risk to this species.

Snapping Turtle management plan (PDF 1.2 MB)

Spotted Pondweed vulnerable

Potamogeton pulcher - 2013

Spotted Pondweed is a freshwater aquatic plant and a member of the Atlantic Coastal Plain Flora found almost exclusively in SW Nova Scotia. Potamogeton pulcher is found in only 12 populations in the province, 8 of which are in Queens and Lunenburg County where it does well in highly acidic, nutrient poor wetlands. The most imminent threats to Spotted Pondweed are any activities that change water quality or quantity including those that may eutrophy water.

Spotted Pondweed is a freshwater aquatic plant and a member of the Atlantic Coastal Plain Flora found almost exclusively in SW Nova Scotia. Potamogeton pulcher is found in only 12 populations in the province, 8 of which are in Queens and Lunenburg County where it does well in highly acidic, nutrient poor wetlands. The most imminent threats to Spotted Pondweed are any activities that change water quality or quantity including those that may eutrophy water.

Sweet Pepperbush vulnerable

Clethra alnifolia - 2000

An Atlantic Coastal Plain species of shrub that is found in Canada only on six lakeshores in southwestern Nova Scotia. Three of these populations, discovered in the past three years, are large and indicate that the plant is more abundant that previously thought. However, there is still concern that this long-lived perennial may have limited sexual reproduction in Nova Scotia, where it is at the northern limit of its range.

An Atlantic Coastal Plain species of shrub that is found in Canada only on six lakeshores in southwestern Nova Scotia. Three of these populations, discovered in the past three years, are large and indicate that the plant is more abundant that previously thought. However, there is still concern that this long-lived perennial may have limited sexual reproduction in Nova Scotia, where it is at the northern limit of its range.

Tall beakrush vulnerable

Rhynchospora macrostachya - 2017

In Canada, this perennial sedge is known only to occur at two lakeshore wetlands, both located in southwestern Nova Scotia. The plants in Nova Scotia are an isolated pocket that has been geographically separated from the main population of Tall beakrush growing along the U.S. Atlantic coast. Tall beakrush is Endangered in Nova Scotia because of its relatively low abundance, highly concentrated distribution, and its vulnerability to disturbance from events such as lakefront development, water level regulation, and competition from other plants.

In Canada, this perennial sedge is known only to occur at two lakeshore wetlands, both located in southwestern Nova Scotia. The plants in Nova Scotia are an isolated pocket that has been geographically separated from the main population of Tall beakrush growing along the U.S. Atlantic coast. Tall beakrush is Endangered in Nova Scotia because of its relatively low abundance, highly concentrated distribution, and its vulnerability to disturbance from events such as lakefront development, water level regulation, and competition from other plants.

Tall beakrush recovery plan (PDF 3 MB)

Thread-leaved Sundew endangered

Drosera filiformis - 2000

This Atlantic Coastal Plain plant species is found in Canada in only five wetland bogs in southwestern Nova Scotia. Threats to this species include the draining, alteration and development of bog habitats.

This Atlantic Coastal Plain plant species is found in Canada in only five wetland bogs in southwestern Nova Scotia. Threats to this species include the draining, alteration and development of bog habitats.

Thread-leaved Sundew recovery plan (PDF 3 MB)

Transverse Lady Beetle endangered

Coccinella transversoguttata - 2017

Prior to 1980, the Transverse lady beetle was the most common native ladybug in the province and most widely distributed across Canada. The arrival of the non-native Seven spotted lady beetle corresponded with a rapid decline in abundance and geographic range of the Transverse lady beetle, and may have forced the Transverse lady beetle to retreat to more specific habitat types. Although still abundant in western Canada, it remains uncertain whether the species is still present in the parts of eastern Canada, including Nova Scotia.

Prior to 1980, the Transverse lady beetle was the most common native ladybug in the province and most widely distributed across Canada. The arrival of the non-native Seven spotted lady beetle corresponded with a rapid decline in abundance and geographic range of the Transverse lady beetle, and may have forced the Transverse lady beetle to retreat to more specific habitat types. Although still abundant in western Canada, it remains uncertain whether the species is still present in the parts of eastern Canada, including Nova Scotia.

Transverse Lady Beetle recovery plan (PDF 2 MB)

Tri-colored Bat endangered

Perimyotis subflavus - 2013

The Tri-colored Bat, or Eastern Pipistrelle is the rarest of three congregatory bats that occur in the province. The Nova Scotia population is thought to be geographically isolated (disjunct) from others in eastern North America. Little is known about the ecology of tri-colored bats in the province, but research shows that it uses rivers and streams for feeding. Although white-nose syndrome has not been confirmed in this species in Nova Scotia (likely because the bat was always rare), evidence in the north east US indicates the species has been seriously impacted. White-nose-Syndrome is caused by the fungus, Geomyces destructans. There is no known cure for the disease which is lethal and affects all bat species that congregate during hibernation.

The Tri-colored Bat, or Eastern Pipistrelle is the rarest of three congregatory bats that occur in the province. The Nova Scotia population is thought to be geographically isolated (disjunct) from others in eastern North America. Little is known about the ecology of tri-colored bats in the province, but research shows that it uses rivers and streams for feeding. Although white-nose syndrome has not been confirmed in this species in Nova Scotia (likely because the bat was always rare), evidence in the north east US indicates the species has been seriously impacted. White-nose-Syndrome is caused by the fungus, Geomyces destructans. There is no known cure for the disease which is lethal and affects all bat species that congregate during hibernation.

Tri-colored Bat recovery plan (PDF 19 MB)

Tubercled Spikerush vulnerable

Eleocharis tuberculosa - 2013

This Atlantic Coastal Plain plant species is found in Canada on the shores of only five lakes in Nova Scotia. One population is considered a distinct endemic form (E. tuberculosa, forma pubnicoensis) Some populations of this species in the United States are also at risk. Threats to this species are linked to: its small, very localized populations, human alteration and loss of lakeshore habitats, destruction of populations and habitat by ATV's and other recreational activities.

This Atlantic Coastal Plain plant species is found in Canada on the shores of only five lakes in Nova Scotia. One population is considered a distinct endemic form (E. tuberculosa, forma pubnicoensis) Some populations of this species in the United States are also at risk. Threats to this species are linked to: its small, very localized populations, human alteration and loss of lakeshore habitats, destruction of populations and habitat by ATV's and other recreational activities.

Vole Ears endangered

Erioderma mollissimum - 2013

In Canada, Vole's Ears lichen is known from Newfoundland, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. The lichen occupies cool, moist spruce/fir forests and in Nova Scotia is known from 20 sites with only 118 thalli. An 80% decline in the number of sites has been recorded. Vole's Ears is extremely sensitive to air born pollution and acid rain, but is also threatened by forest harvesting.

In Canada, Vole's Ears lichen is known from Newfoundland, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. The lichen occupies cool, moist spruce/fir forests and in Nova Scotia is known from 20 sites with only 118 thalli. An 80% decline in the number of sites has been recorded. Vole's Ears is extremely sensitive to air born pollution and acid rain, but is also threatened by forest harvesting.

Vole Ears recovery plan (PDF 6 MB)

Water Pennywort endangered

Hydrocotyle umbellata - 2001

An aquatic species of Atlantic Coastal Plain species known in Canada only from two lakeshores in southwestern Nova Scotia. One of these populations is within Kejimkujik National Park and is protected. Research has recently verified that these plants are not capable of sexual reproduction and the species persists here only through asexual reproduction. The abundance of this species can vary dramatically at these sites over time. Threats to the species include shoreline alteration, human and vehicle disturbance and eutrophication (nutrient enrichment).

An aquatic species of Atlantic Coastal Plain species known in Canada only from two lakeshores in southwestern Nova Scotia. One of these populations is within Kejimkujik National Park and is protected. Research has recently verified that these plants are not capable of sexual reproduction and the species persists here only through asexual reproduction. The abundance of this species can vary dramatically at these sites over time. Threats to the species include shoreline alteration, human and vehicle disturbance and eutrophication (nutrient enrichment).

Water Pennywort recovery plan (PDF 3 MB)

Wood Turtle threatened

Clemmys insculpta - 2013

There may be 2,500 Wood Turtles widely dispersed across river habitats in Nova Scotia, but information suggests that this species is declining. Like other turtles, this species is of concern because even low mortality rates of adults can have serious population impacts. Threats to wood turtles in Nova Scotia include alteration and destruction of river and stream habitats and translocations of turtles by people. (click image for larger pictures)

There may be 2,500 Wood Turtles widely dispersed across river habitats in Nova Scotia, but information suggests that this species is declining. Like other turtles, this species is of concern because even low mortality rates of adults can have serious population impacts. Threats to wood turtles in Nova Scotia include alteration and destruction of river and stream habitats and translocations of turtles by people. (click image for larger pictures)

Wood Turtle recovery plan (PDF 2 MB)

Wrinkled Shingle Lichen threatened

Pannaria lurida - 2017

Wrinkled shingle lichen is a leafy brownish grey wrinkled lichen that grows in wet areas and almost exclusively on the trunks of mature deciduous trees, usually Red maple. Its reproductive cycle is highly specialized involving pairing with a unique type of bacteria that is capable both of photosynthesis and extracting nitrogen (nutrients) from the air. The entire Canadian population occurs in Atlantic Canada, 90% of which is present in Nova Scotia. Scientists estimate that the species has declined by 30% over the past thirty years. The major threat to the species is forest harvesting, followed by other land development activities, climate change, and air pollution.

Wrinkled shingle lichen is a leafy brownish grey wrinkled lichen that grows in wet areas and almost exclusively on the trunks of mature deciduous trees, usually Red maple. Its reproductive cycle is highly specialized involving pairing with a unique type of bacteria that is capable both of photosynthesis and extracting nitrogen (nutrients) from the air. The entire Canadian population occurs in Atlantic Canada, 90% of which is present in Nova Scotia. Scientists estimate that the species has declined by 30% over the past thirty years. The major threat to the species is forest harvesting, followed by other land development activities, climate change, and air pollution.

Yellow Lampmussel threatened

Lampsilis cariosa - 2006

A species of freshwater mussel found in Canada on only two rivers including the Sydney River, Nova Scotia. The current population is large and apparently stable, but confined to a small area. Threats are currently limited, but the very small and discontinuous range of this species in Nova Scotia makes it vulnerable to pollution and degradation of habitat.

A species of freshwater mussel found in Canada on only two rivers including the Sydney River, Nova Scotia. The current population is large and apparently stable, but confined to a small area. Threats are currently limited, but the very small and discontinuous range of this species in Nova Scotia makes it vulnerable to pollution and degradation of habitat.

Yellow Lampmussel recovery plan (PDF 1.95 MB)

Yellow-banded Bumble Bee vulnerable

Bombus terricola - 2017

The Yellow-banded bumble bee is adaptable, occurring through most of Canada and in a wide variety of habitats. It remains an important pollinator of cultivated crops and native plants. Nest sites are usually underground in soil cavities or rotting logs. Why this once common widespread species is significantly declining in parts of its range is unclear, but probably due to a combination of factors. Threats include competition and disease from other actively managed introduced bumble bee species; use of pesticides; climate change; and habitat loss caused by urbanization.

The Yellow-banded bumble bee is adaptable, occurring through most of Canada and in a wide variety of habitats. It remains an important pollinator of cultivated crops and native plants. Nest sites are usually underground in soil cavities or rotting logs. Why this once common widespread species is significantly declining in parts of its range is unclear, but probably due to a combination of factors. Threats include competition and disease from other actively managed introduced bumble bee species; use of pesticides; climate change; and habitat loss caused by urbanization.

Yellow-banded bumble bee management plan (PDF 2.1 MB)

The Cape Breton population of Marten is likely less than 50 animals. At present there is no evidence of breeding and there has been extensive loss and degradation of suitable habitat. Marten were trapped extensively throughout Nova Scotia since the 1700's until the season was closed in the early 1900's due to low numbers. The species was thought to have been extirpated from the mainland and several re-introductions have been attempted. There have been some very recent records of Marten in southwest Nova Scotia. However, the status of the Marten on the mainland is considered "data deficient." More research is required.

The Cape Breton population of Marten is likely less than 50 animals. At present there is no evidence of breeding and there has been extensive loss and degradation of suitable habitat. Marten were trapped extensively throughout Nova Scotia since the 1700's until the season was closed in the early 1900's due to low numbers. The species was thought to have been extirpated from the mainland and several re-introductions have been attempted. There have been some very recent records of Marten in southwest Nova Scotia. However, the status of the Marten on the mainland is considered "data deficient." More research is required.

The Atlantic whitefish is a species endemic to Nova Scotia, meaning that it breeds nowhere else in the world. In Nova Scotia it is found only in the Tusket and Petite Riviere watersheds and may have been extirpated from the Tusket River system. Little is known about this species and no population estimate for the species exists. Past and present threats to the species include: hydro-electric development, predation by non-native fish species (e.g. chain pickerel, smallmouth bass), acidification and fishing.

The Atlantic whitefish is a species endemic to Nova Scotia, meaning that it breeds nowhere else in the world. In Nova Scotia it is found only in the Tusket and Petite Riviere watersheds and may have been extirpated from the Tusket River system. Little is known about this species and no population estimate for the species exists. Past and present threats to the species include: hydro-electric development, predation by non-native fish species (e.g. chain pickerel, smallmouth bass), acidification and fishing.

The Bank swallow is a small brown bird that feeds almost exclusively on flying insects. This swallow breeds in colonies and excavates nesting burrows in the eroding banks of coastal cliffs and other steep vertical soft soil faces, such as gravel pits. Their numbers have declined by about 30% over the past 10 years across Canada, and considerably more in Nova Scotia. A combination of factors, including loss of nesting habitat, reduced availability of insects, and threats encountered along the winter migration route and at overwintering areas in South America, have reduced the abundance of Bank swallows.

The Bank swallow is a small brown bird that feeds almost exclusively on flying insects. This swallow breeds in colonies and excavates nesting burrows in the eroding banks of coastal cliffs and other steep vertical soft soil faces, such as gravel pits. Their numbers have declined by about 30% over the past 10 years across Canada, and considerably more in Nova Scotia. A combination of factors, including loss of nesting habitat, reduced availability of insects, and threats encountered along the winter migration route and at overwintering areas in South America, have reduced the abundance of Bank swallows.

Barn Swallows were one of the world`s most widespread species, but have undergone continental level declines across North America begining in the 1980s. Loss of important nesting sites in the wake of changing agricultural practices (barns) and other artificial structures such as bridges maybe implicated with declines. Concurrent declines of many other aerial insectivorous birds in Nova Scotia and throughout North America suggest changes in the insect food base and climate change may also be implicated. While actual mechanisms of the decline are not well understood the rapidity and geographic extent are cause for concern.