by: Bob Bancroft

FALL 1988

Lakes and streams throughout Nova Scotia offer opportunities for a wide variety of animals, from moose to salamanders. Forested lands bordering these areas provide some of the best habitat or living areas for our wildlife species. This article takes a fresh look at forestry practices on lands near waterways.

Buffer strips along waterways should be considered Special Management Zones (SMZ) where shelterwood, strip and patch cutting and other alternatives to large scale clearcutting can be employed. This approach would maintain fish and wildlife habitats while still offering forestry benefits - a vital concern, since good timber is often found along watercourses.

Woodlot owners can easily find a great deal of material about woodlot management. but finding information about managing wildlife on woodlots is not so easy.

In order to plan a SMZ along a watercourse the woodlot owner should study the variety of wildlife using the area. frequent walks through your woodlot will reveal tracks in the mud or snow, browsed plants, and droppings. glimpses of the disappearing creatures can also help you discover the animals that share your forest. Identification guides are a worthwhile investment. Some of these are available through the Department of Lands and Forests, the Nova Scotia Museum and various recreation associations. As you develop an understanding of the wildlife species in your woodlot, your forest management planning can be expanded to include provisions for wildlife.

The width of SMZs can vary from 10 to 330 feet or more (3 to 100 metres) on each side of a waterway. base your width selection on the following factors:

Land Sensitivity

Soil Type: Streams flow through areas with different soils. Some soils erode more easily than others; disturbing such soils can result in stream siltation. thus clay soils can create more silt than sandy soils. Soil maps can be purchased from book stores to assist you. You may need to dig some holes near your stream or lake and pour some water on to the exposed soil pit to determine the sensitivity of the site.

Water table: It is also important to determine how close the water levels in your soils are to the ground surface. this varies with the time of year. Most woodlot owners who have been stuck with their machinery can spot wet areas and are willing to work around them.

Slope: The slope of the land near your stream or lake is also important. Steeper slopes require a wider SMZ to prevent silt from crossing the buffer strip and destroying good fish habitat.

Solar Sensitivity

Trout and salmon thrive in water temperatures between 57° and 61°F (14-16°C). As water temperatures rise, the oxygen available for fish decreases. When water temperatures exceed 72°F (22°C), trout and salmon begin to die. In Nova Scotia summer water temperatures above 86°F (30°C) are common in rivers and open streams. Unless your brook is supplied by cold spring water, forest shade is essential for trout and salmon to survive. Leaving trees along a stream will keep temperatures cool enough for young trout and salmon. The shade provided by individual trees varies with sizes, shape and species, and by their position in relation to our summer sun. For example, the south side provides most of the shade for a brook flowing in an east-west direction. The north side may not offer much shade, but is the side favoured by overwintering deer since it faces south. brooks oriented north-south are shaded by trees on both sides.

|

|

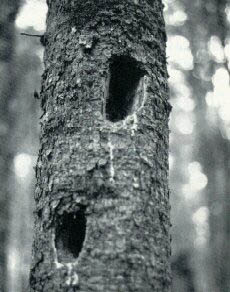

| Blowdown resulting from poor cutting practices near stream edge | Cavities in a "snag" or standing dead tree. |

Woodlot owners considering SMZs along waterways must also consider wind and storm damage. It is common for overmature mixed wood (hardwood and softwood) forest, and pure softwood forests exposed by clearcutting, to blow down. The same is true of younger, closely spaced stands with small, competing root systems. Softwoods are shallow-rooted. Many well-intentioned one-tree-wide buffers along small brooks serve to keep machinery out of the brook, but fall down in autumn storms. These small brooks cane important habitat for young trout - even where the water partially dries up in summer.

Younger stands of trees along a watercourse can be cleaned or spaced to strengthen their roots. Where over-mature wood borders a stream or lake, the SMZ may have to be widened to minimize blowdown. A few trees falling on a brook can create good fish habitat by creating pools. but if they all uproot and fall over at once, the channel may widen, the water may become shallow, and cover from predators can be lost. If a SMZ of overmature trees is left, the softwood could be harvested gradually. In that process young trees would gradually establish in the spaces left.

Research is under way to determine effective SMZ widths for varying soil and site conditions. The St. Mary's River Forestry-Wildlife Project is a joint venture among many interested parties, including the Canadian Institute of Forestry (N.S. Section), Forestry Canada, Scott Maritimes Limited, Stora Forest Industries and the N.S. Department of Lands and Forests.

You should also consider leaving dead and dying trees or very old trees along waterways. Up to one-quarter of our wildlife species use these trees. This use continues when the old trees finally topple to the ground. Eventually their nutrients are recycled and become a new forest. Leaving old trees in your SMZ will attract species like woodpeckers, which chip our nests that later become important shelter and nest holes for other wildlife species such as owls and flying squirrels. Bald eagles and other birds favour tall old hardwoods and white pines for nest building.

Careful management of edges of waterways will benefit more than wildlife. It will make your woodlot a more fascinating place.