The Economics and Statistics Division maintains archives of previous publications for accountability purposes, but makes no updates to keep these documents current with the latest data revisions from Statistics Canada. As a result, information in older documents may not be accurate. Please exercise caution when referring to older documents. For the latest information and historical data, please contact the individual listed to the right.

<--- Return to Archive

For additional information relating to this article, please contact:

June 24, 2020FOOD SECURITY DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC, MAY 2020 Today, Statistics Canada released the results of the second wave of the Canadian Perspectives Survey Series (CPSS) which included a series of questions aimed at assessing the levels of food insecurity being experienced by Canadians.

From May 4 to 10, 2020, 4,600 respondents from all 10 provinces participated in the CPSS. Because the CPSS targets a subsample of the Labour Force Survey (LFS) sample, the variable indicating presence of children in the household was drawn from the LFS data. All of the differences presented in this release between the population subgroups are significant at the 5% level (p<0.05).

To assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on food security, the results of the recent Canadian Perspectives Survey Series from May 4 to 10 was compared to the results from the Canadian Community Heath Survey for the 2017/2018 reference period. While there are important differences between the two survey designs and questions on food insecurity, the study finds that there has been an increase in food insecurity.

Around one in seven (14.6%) Canadians reported that they lived in a household with food insecurity in the past 30 days. Food insecurity was reported on a scale of six experiences ranging from food not lasting before there was money to buy more, to going hungry because there was not enough money for food. Most Canadians reported only one negative experience while 2.0 per cent of respondents reported the most severe food insecurity with five or all six experiences reported.

Statistics Canada noted that the estimate from the web panel were likely a conservative estimate of food insecurity in Canada at the time the data was collected due to two factors. First, the evaluation of the web panel sample showed that the survey underrepresents certain populations that are known to be vulnerable to food insecurity (e.g. those who are divorced/widowed/separated, those who are renters, and those in the types of occupations in industries where working from home is less possible). Second, studies in the USA where both the 10-day and 12-month questionnaires have been used, show that the 10-day time frame tends to obtain a lower rate of food insecurity.

In comparison, the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) showed that 8.8 per cent of Canadian households - approximately 1.2 million - experienced some moderate or severe food insecurity due to financial constraints in 2017-2018. Food insecurity exists when household members report having issues with the quality or quantity of food consumed (moderate food insecurity) or having experienced reduced food intake or disrupted eating pattern (severe food insecurity).

While the CCHS included a more detailed 18-item food security module and were based on the past 12-month experiences, when accounting for the six common questions between the CHSS and the web panel survey, the results show that food insecurity is significantly higher during COVID-19 in comparison to the 2017/2018 results; 14.6 per cent versus 10.5 per cent respectively.

19.2 per cent of Canadians living in a household with children reported food insecurity compared to 12.2 per cent of those living with no children. In particular, when compared to households with no children, Canadians living in households with children (13%) were more likely to be worried about food running out before there was money to buy more and having difficulty affording to eat balanced meals.

Canadians who were employed during the week of April 26th to May 2nd, but absent from work due to business closure, layoff, or personal circumstances due to COVID-19, were more likely to be food insecure (28.4%) than those who were working (10.7%). The rate of food insecurity for those who were not employed during the reference week was in between these two rates at 16.8 per cent.

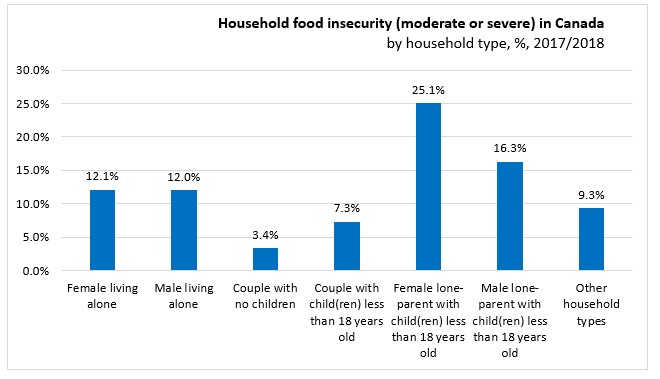

Household food insecurity, 2017/2018

Moderate and severe household food insecurity varied by family type. The proportion of households that experienced food insecurity was over twice as high for lone-parent families with children than for couples with children. Among households with children, female lone-parent families were the most likely to experience food insecurity (25.1%), followed by male lone-parent families (16.3%) and couples with children (7.3%).

Households in Canada consisting of a couple living alone were the least likely to experience food insecurity (3.4%). Among single-person households, females and males experienced a similar rate of moderate or severe food insecurity (about 12%).

Household food insecurity (moderate or severe) differs between provinces and territories. Food insecurity was highest among households in Nunavut with 49.4% experiencing food insecurity (about 25.8% moderate and 23.7% severe food insecurity).

Rates of food insecurity were also higher than the national average in Nova Scotia (11.0%), Manitoba (10.2%), Yukon (12.6%), and Northwest Territories (16.0%). Quebec (7.4%) was the only province/territory with a lower proportion of households experiencing food insecurity than the average. All other provinces had rates of food insecurity similar to the national average.

Source: Statistics Canada, Food security during the COVID-19 pandemic, May 2020; Household food insecurity, 2017/2018

<--- Return to Archive