By Jerry Lockett

JANUARY 2001

Date of Post: July 2003

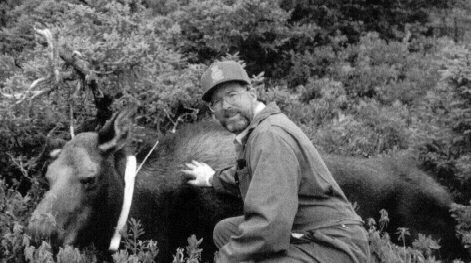

In October Derek Quann bagged his first moose. He wasn't hunting, but tranquilizing the animal with an anaesthetic dart fired from a helicopter. "There's not much time for the darter and pilot to talk," he says. "You only have a second or two of opportunity. It's important not to traumatize the animal, and within a few minutes it went down in its chest with legs folded, which is the best way." On the ground he fitted it with a radio collar and ear tags, made sure it was OK, and injected another drug to reverse the anaesthetic before seeing it on its way. He will repeat the process 18 times this winter.

It's all part of a new five year study, a joint project between Parks Canada and DNR, intended to ensure that a healthy and viable moose population will be maintained throughout their natural range in northern Cape Breton. Derek, a warden in Cape Breton Highlands National Park, is the project's Fieldwork Coordinator. Once the moose are collared he will be monitoring and tracking their movements and activities. Some of the radio collars carry only a VHF transmitter and will be located regularly using aircraft. Others will also carry a GPS receiver and computer that obtain a position every three hours and store that information. DNR is providing helicopter support, field assistance, and technical and scientific expertise. Members of the aboriginal community will also be involved in the field and technical work.

"Moose seem abundant in northern Cape Breton at this time," says Tony Nette, DNR's Manager of Wildlife Resources responsible for big game," but we need to determine what a total appropriate harvest level is. To do that we need to know how many moose there are, the age and sex make up of the herd, where they are, what condition they are in, their rate of reproduction and the rate of herd growth. This hasn't been done before in any detail.

There has been a provincially licensed hunt of 200 moose in Victoria and Inverness counties every year since 1986, as well as a significant harvest by First Nations people. The figure of 200 moose is conservative, based on uncertain population estimates. "We are confident that the herd has not been harvested beyond a sustainable level to date," says Tony Nette. "We think that numbers are now approaching their optimum, but whether they will remain stable or decline sharply remains to be seen." In recent years 90 per cent of the licensed hunt target has been achieved. This is very high in hunting terms, and much of the hunt takes place in only a limited part of the range. Many areas are simply inaccessible, and there is no legal hunting within the National Park.

The VHF collars will stay on the animals for several years, allowing researchers to follow and find individual moose at any time. The more expensive GPS collars have a remote release buckle that will be triggered from a distance after about one year. After the stored location data has been retrieved, these GPS collars can be given new batteries and reused. The biologists hope to monitor 80 moose over the course of the study, 40 with GPS collars and 40 with VHF collars. These animals should provide much valuable information that will help give a better understanding of the moose population.