New Information on an Overlooked Group of Animals

by Jerry Lockett

JANUARY 2001

Date of Post: July 2003

Nova Scotia is home to a fascinating variety of wildlife, but not all these creatures are as familiar as the bald eagle or as charismatic as the lynx. It's easy to overlook less glamorous species - probably very few Nova Scotians even know that our province is home to several types of freshwater mussel, let alone that biologists fear for the mussels' future.

In North America there are more than 300 species of freshwater mussel, but Nova Scotia is at the northern edge of their range, and we have only ten. This entire group of bivalve molluscs is threatened throughout the continent by a number of human activities, but until now only patchy data has been available on the number and whereabouts of each species in our province. "Absence of information is a real concern with this group of organisms. We don't even know if we have any species, because there has been no monitoring system in place," says Mark Elderkin, DNR's Species at Risk Biologist.

He decided that it was time for a new survey - the last one of any size was carried out almost forty years ago - and enlisted the help of five of DNR's Regional Biologists who share his concern for these molluscs. Over the last two years they have surveyed freshwater mussel populations in Antigonish, Colchester, Halifax, Inverness, Victoria, Cape Breton, and Richmond counties. With the help of summer students, the biologists sampled rivers and lakes in their regions and recorded the results. "This is the most comprehensive survey ever carried out in the province," says Mark Pulsifer, regional biologist for Antigonish and Guysborough counties. "So far we have surveyed about 450 sites in northern and eastern Nova Scotia. We've added three new species to the list for Antigonish county. We have also discovered that one species, the Triangle Floater, is not nearly as common as was previously perceived."

This survey will provide the biologists with a baseline of information. They hope to publish their results this winter to provide a benchmark for eastern Canada. In future they will be able to track and monitor sites where there is a low occurrence of species - such as the Delicate Lamp Mussel - to see whether numbers are stable, increasing, or decreasing. This will help them decide what conservation measures may be necessary.

Freshwater mussels are easy to spot along riverways where they occur, but they can be difficult to identify, as members of the same species can differ greatly in appearance. Derek Davis, formerly Chief Curator of Natural History at the Nova Scotia Museum, has provided expert help in identifications, as well as in molluscan biology and ecology. So far the survey work has been restricted to the shallow borders of lakes and waterways - sampling deeper waters will require SCUBA capability.

Freshwater mussels face several threats. Chemical pollution of waterways and sitration due to soil erosion are two causes for concern. These organisms feed by filtering large volumes of water, and they tend to accumulate pollutants - such as heavy metals - in their body tissues. During the survey, specimen shells were deposited in Nova Scotia Museums collections so that future comparisons of toxin levels can be made. In central Canada, Zebra Mussels introduced from Europe are displacing native species, and these alien invaders could make their way to Nova Scotia. Dams are especially harmful. They destroy riffle habitats - the shallow, well-aerated rapids that are a favorite haunt of many species. The deep waters behind dams, however, become stagnant and low in oxygen.

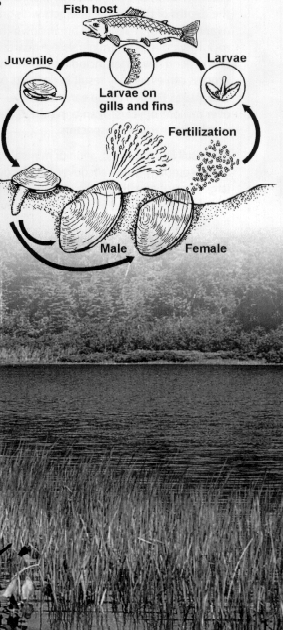

Damming has another - indirect - effect on freshwater mussels, because of a peculiarity in their life history. Mussel larvae need to find a temporary home in the gills or on the fins of a salmon or trout, before they become juveniles and settle down on the bottom of a river or lake. They do little harm to the fish, and get a free ride that helps them disperse. But damming can block the free passage of the mussels' host fish.

This is exactly what happened when a causeway was built across the Petitcodiac River in New Brunswick in 1968". It removed the fish that were hosts to mussels," says Mark Elderkin," and now the Dwarf Wedgemussel is extirpated (no longer found) on that river, which was one of the only sites in Canada where it was known. Without careful attention to the broad ecology of rivers, brooks, and watersheds, an action that seems initially to affect only one species, such as salmon or trout, may result in another species being lost further down the ecological chain."